Skip header and jump directly to primary site navigation.

Skip header and jump directly to primary site navigation.

Ventura County Medical Center Hospital Replacement Wing

March, 2021 - LEAN IN DESIGN-BUILD SERIES

Using Data Analytics to Drive Value and Improvement

By Betty Lynn Senes, Project Director, Sundt Construction

Why are Lean practices important?

As an industry, we need to improve. We need to provide better value for our clients. We do not hit schedule or budget targets as reliably as we think. A study from FMI and Autodesk, “Trust Matters: The High Cost of Low Trust” recently reported that “In the US alone, according to FMI, the cost of missed schedules is estimated to be $20 billion per year, excluding single-family construction projects.” Another study, “The Business Case for Lean”, from LCI/Dodge/McGraw Hill", indicates that 61% of “Typical Projects” complete behind schedule and 49% of “Typical Projects” complete over budget. Poor productivity, inefficient communication, or unplanned events or obstacles are just a few reasons for this. Embracing Lean philosophy and practices are shown to make a substantial difference, in comparison. The authors of “Business Case for Lean” article found that only 21% of projects with intense Lean practices completed behind schedule, and only 17% over budget.

The Deming Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle is the model used in Lean circles to talk about continual improvement. Expressed a different way, the cycle means: “plan, perform, monitor, and improve”. When we “check” after acting, or “monitor” after “performing,” we are using the past to predict and potentially modify events of the future. We are increasingly able to track project metrics. With the exponential growth of technology, use of more apps, and the advent of “big data”, data analytics is becoming more accessible and more important than ever.

Wikipedia defines “analytics” as “the systemic computational analysis of data or statistics. It is used for the discovery, interpretation, and communication of meaningful patterns in data.” Data Analytics can (a) help us verify and understand the current state, (b) illustrate trends we may not currently be aware of, (c) provide intelligent insights, and (d) help us prioritize problems or root causes; all for more informed and deliberate decision making.

How can data analytics help?

Real-time data analytics can generate credibility, which leads to trust and higher performing teams, another common Lean concept. FMI/Autodesk’s “Trust Matters” asserts that “technology can create trust, by improving transparency, enhancing communication, and providing evidence of success.” Data illustrating trends and patterns visually can effectively raise awareness and motivate change. The actual data that contributes to the message also brings credibility to the message. An example from the pull planning process would be pointing out to a trade: “you achieved 81% of your planned percent complete over the past 3 months”, or “you have made only 50% of your commitments over the past 3 months.” Delivered among a group of trades, a competitive spirit develops that helps motivate the team. The real-time, accurate information removes the obstacles that subjective statements sometimes pose and the disagreements that often disrupt progress.

The more quickly we obtain, process, and visualize current information, the faster we can exchange ideas, and the more effective we are at improving outcomes.

Examples

Continual improvement and value-add through data analytics can come in many forms. Some examples are:

Following is an exploration of these concepts to provide insights on what one firm in the AEC industry is doing to harness the power of data.

Safety Performance

Tracking safety performance, inspections, and incidents has led to a significant improvement in Recordable Incident Rate for one firm. “Sundt Construction Analytics” (“SCA”) allows tracking of observations of safe and unsafe conditions using a mobile phone, iPad, or laptop computer. The data that is collected, analyzed, and presented visually has illustrated strengths and areas to improve. After collecting several years of data, the exercise has also yielded predictive tools. The projects and tasks of highest anticipated risk are forecast, and leaders are mobilized to ensure safety practices are the highest priority there. Trending graphs and spotlights on the best performers (by project site, office, region, or group), along with an initiative on “Relentless Housekeeping,” have resulted in cutting their Recordable Incident Rate by over 75%, from 1.0 in 2016 to 0.23 in 2020. OSHA TRIR for overall U.S. construction in 2019 was 2.8. Building construction composite was 2.5.

Tracking safety performance, inspections, and incidents has led to a significant improvement in Recordable Incident Rate for one firm. “Sundt Construction Analytics” (“SCA”) allows tracking of observations of safe and unsafe conditions using a mobile phone, iPad, or laptop computer. The data that is collected, analyzed, and presented visually has illustrated strengths and areas to improve. After collecting several years of data, the exercise has also yielded predictive tools. The projects and tasks of highest anticipated risk are forecast, and leaders are mobilized to ensure safety practices are the highest priority there. Trending graphs and spotlights on the best performers (by project site, office, region, or group), along with an initiative on “Relentless Housekeeping,” have resulted in cutting their Recordable Incident Rate by over 75%, from 1.0 in 2016 to 0.23 in 2020. OSHA TRIR for overall U.S. construction in 2019 was 2.8. Building construction composite was 2.5.

This process did not just result in better OSHA 300 Logs, it saved people’s lives and improved workers’ quality of life. It significantly reduced lost hours. It reduced the cost of incidents. It created incentive for much better housekeeping/safety protocol, which led to more organized jobsites. More organized sites have more efficient workflow and are more likely to succeed on quality and schedule metrics. The bottom line is that this process has added value for Owners.

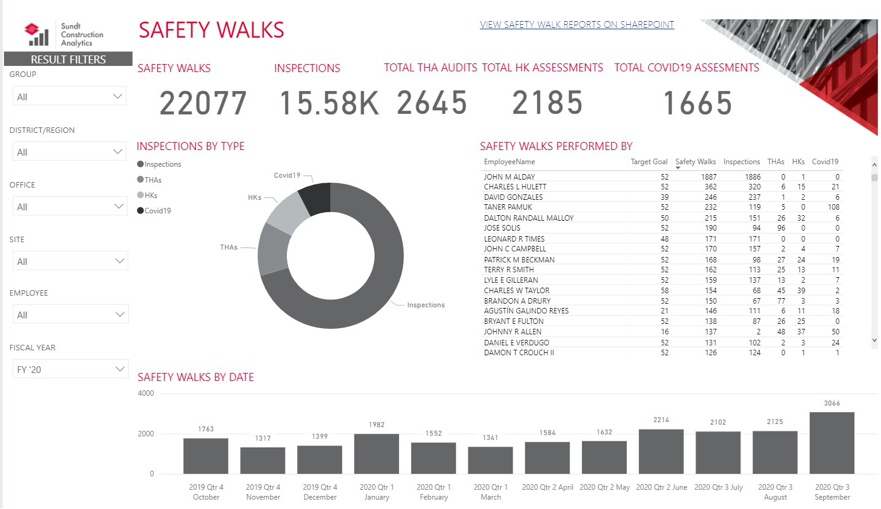

See illustrations, following, highlighting 2020 Safety Scoreboard (Figure 1), and trends in employee safety walks, including outstanding performers (Figure 2).

.jpg)

Figure 2: Safety Scoreboard highlights monthly trends and incident stats. Filters allow viewing by project, office, region, group, and/or year.

Figure 3: Safety Walks Dashboard illustrates staff success at walking, inspecting, and assessing safety conditions. COVID19 assessments were also incorporated to ensure the utmost attention to rigorous jobsite protocols.

Quality Improvements

Similar tools can help eliminate waste and improve the standard of quality that is delivered to Owners. The same firm does this by tracking re-work and corrections. This is not about penalizing people or companies for making mistakes, but about collaboration among all parties on the jobsite to set the stage for success, understanding where additional training may be needed, and providing proactive steps for issues that have come up repeatedly in the past.

These metrics, when filtered by project type, inform the project Quality Management Plan prepared for each specific project. A Subject Matter Expert (“SME”) is assigned to tasks that are more likely to become challenges, to remove potential procurement or rework waste and ensure the best team efforts are applied collaboratively and creatively.

This data also provides learning opportunities for the up-and-coming generation of constructors in the form of “Quality Shares,” or lessons learned. This actionable intelligence is available in a searchable database so that teams just beginning projects, writing trade bid packages, performing quality reviews for constructability, reviewing submittals, or preparing agendas for pre-installation meetings can find information about the scope they are addressing, applying a proactive, quality assurance approach.

This process leads to reduction of rework, cuts down the wasted time coordinating in the field or the administrative time wasted writing, processing, and tracking RFI’s and the subsequent change orders that can result. Harnessing the experience that other teams have already confronted in the past maximizes the firm’s collective knowledge and creates a culture of continual learning in a safe working environment. Ultimately, continuing to improve quality performance adds value.

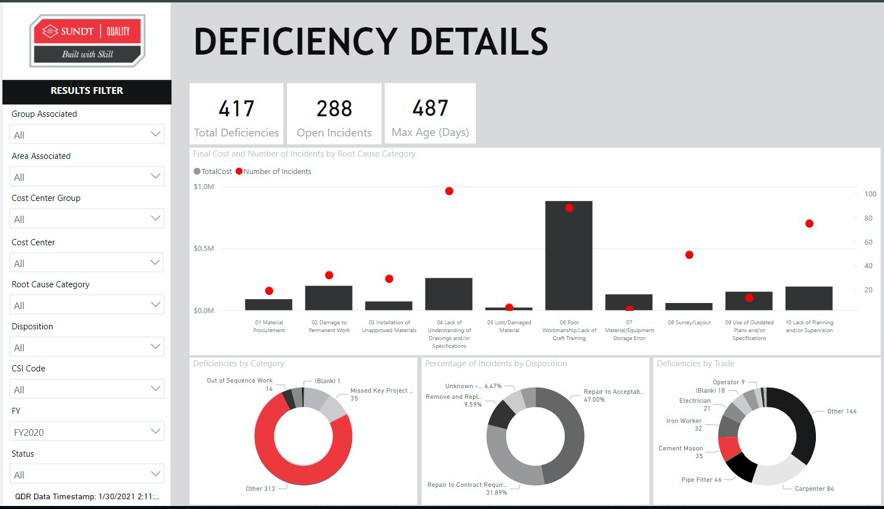

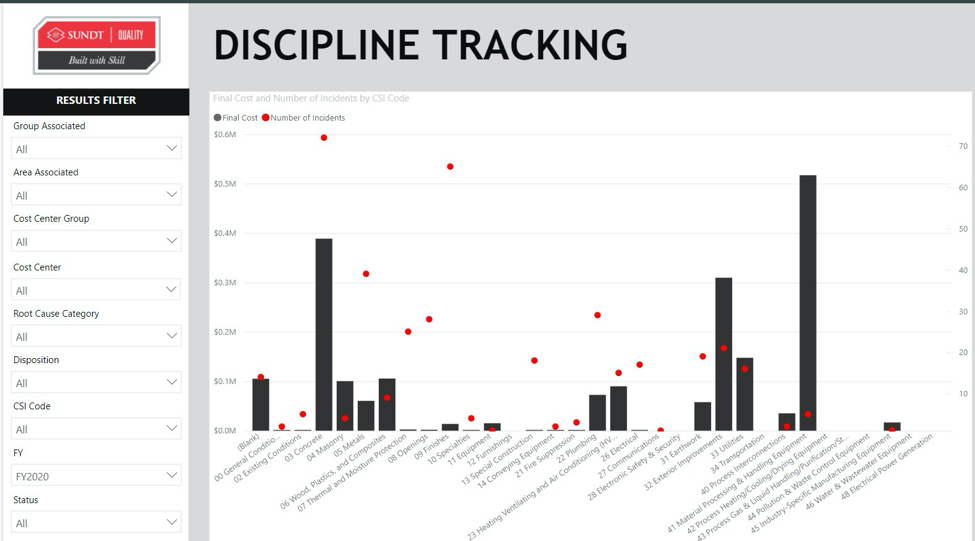

See Figure 4 illustrating quality issues by type, with the ability to filter by project, discipline, area, or group. Figure 5 presents issues by trade, with similar filters. Hovering over any bar will reveal further details of that category, and a drop-down list of those issues.

Figure 4: Deficiency Details proves a closer look as to what types of rework are recurring, and for what reason. This enables the team to be more proactive in planning for success.

Figure 5: Discipline Tracking highlights trades that may have costlier or higher quantity of issues. A Subject Matter Expert ("SME") would be assigned to trades more likely to experience challenges, to remove potential waste and improve schedule outcomes.

Pull Planning Analytics

A third example can be found in the Last Planner ® System (a trademark of the LCI), which is used, especially in Lean practice, to engage the full team of Last Planners on a given project to develop and maintain the project schedule. Last Planners are the trade foremen ultimately responsible for getting the work done, the people closest to the actual work. Their involvement in pull planning is key to its success. Are obstacles being met head on? Is COVID-19 impacting projects, and how can those impacts be mitigated? Which trades are having more success than others? Who needs help? A project manager, foreman, project executive or vice president can get a quick picture, in just a few moments, by looking at graphical representation of several different work planning metrics. Here again, data analytics helps produce visuals of project trends, to get real-time, instantaneous information that drives value.

Pull planning is based on the concept of communication, and pulling activities – from the goal (end of the project), rather than pushing – from the beginning. The main question is “what do you need others to accomplish in order to start your work?” Trades will meet in their Weekly Work Planning meetings, and make promises, or commitments, to have work complete within a certain time. This is much more efficient because the people who are performing work, the ones who know the most about it, are the people doing this planning. Their “reliable promises”, in the pull planning practice, are tracked, along with “planned percent complete” and “reasons for variance”. The data that results from this weekly exercise is invaluable, because it daylights areas of concern to project leaders, so that they can be handled quickly, and obstacles removed right away.

This data has been collected, traditionally, with spreadsheets and Excel charts. Although those sheets and charts have been very useful, the advent of more sophisticated apps and “opportunity” for on-line collaboration, unfortunately due to COVID-19, has allowed us to take this a few steps further. There are several sofware solutions that can be used to manage this data.

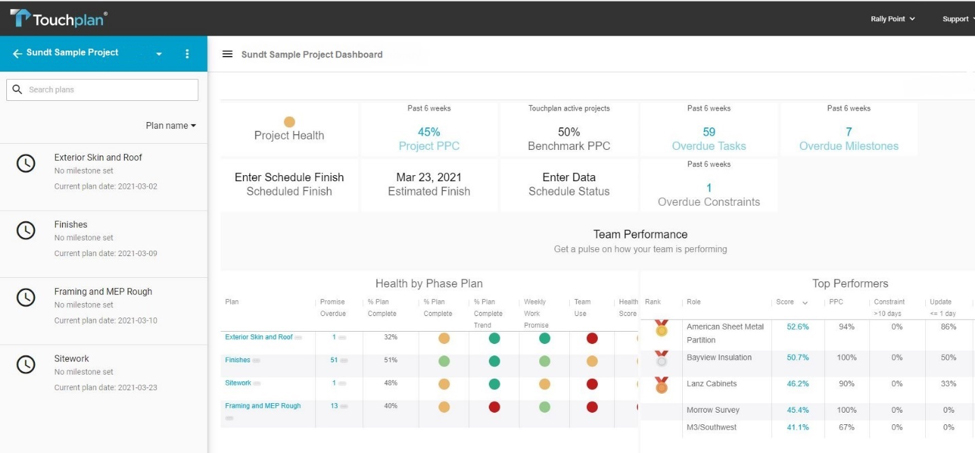

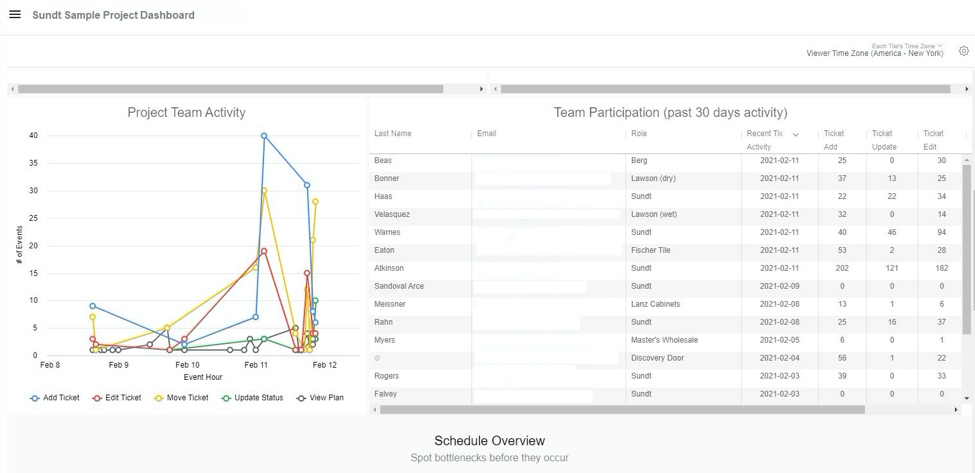

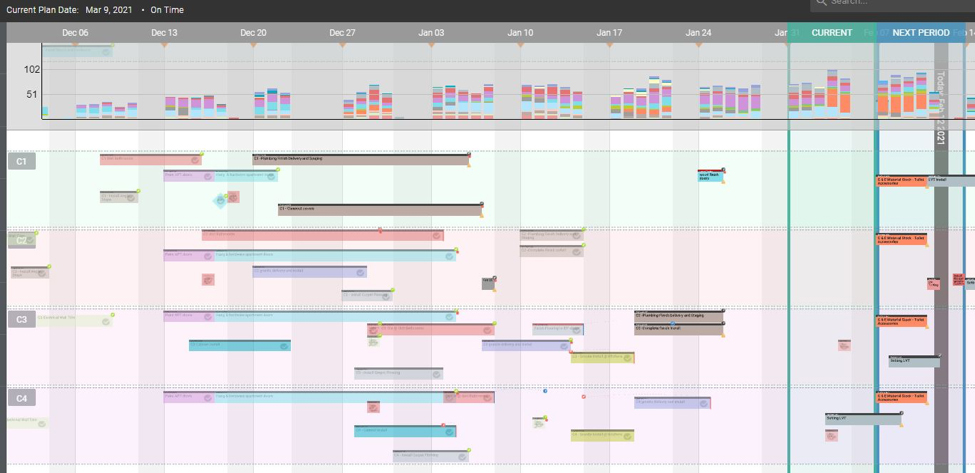

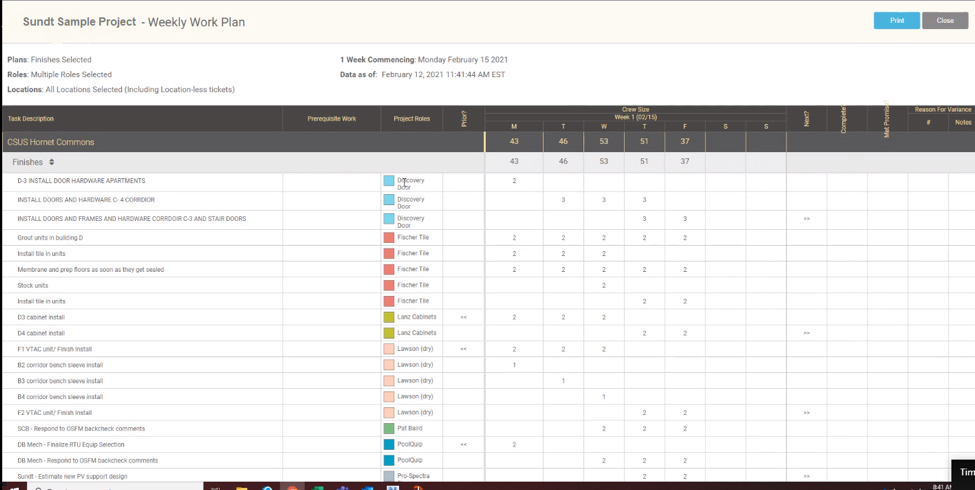

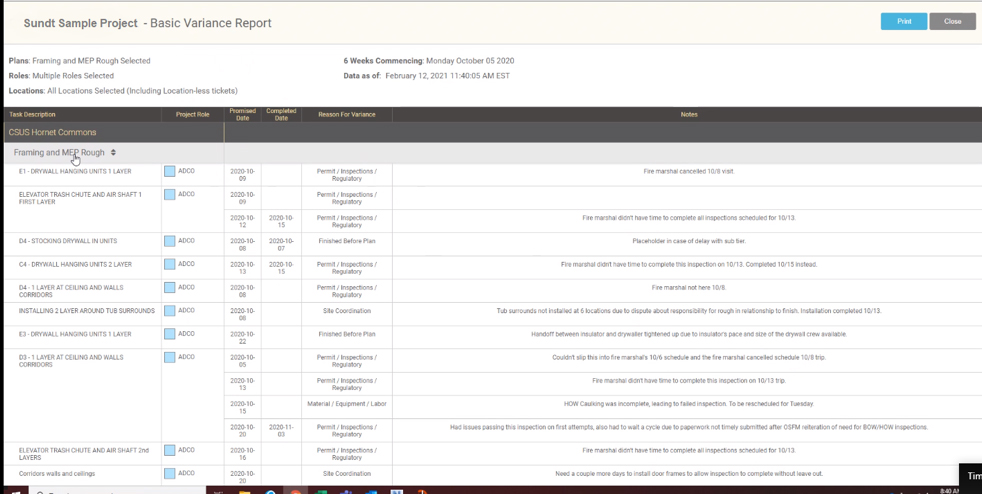

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate two dashboard views. Immediately, the user can see Overdue Tasks, Health by Phase Plan (the red and yellow dots remind the team that updates are needed now), Top Performers, Project Team Activity, and Team Participation. Figure 8 illustrates the “overview” – activities and milestones shown with swim lanes and timeframes. The team can also look at the “Plan for Today” (Figure 9), Weekly Work Plan (Figure 10), a Six-Week Lookahead and more. Figure 11 illustrates activity variance, i.e., why activities were not finished on time. Yet another report tracks manpower by trade, day, and activity. This is another strong tool to help assess progress.

The field teams report that they have shorter, more impactful pull planning meetings. They say that the engagement on the sites using Touchplan, a Last Planner web-based software platform, is up, and that after only two weeks, the Last Planners are largely “all on-board.” Trade contractors indicate they are finding it easy to use, and very helpful in achieving productivity, if each trade “sticks to it.” Project Executives can now have a quick look at what’s going on, and can help them remove obstacles. The real-time data that any team member can see, for example, “promises kept”, and their overdue tasks, removes disputes. The system simply tracks what promises were made, by whom, and what the actual result was. This process eliminates ambiguity, and builds teamwork. Lean is about building high performance teams. The exercise of Pull Planning, with the collection and visual display of data, contribute to the realization of the team goals.

Figure 6: Dashboard 1

Figure 7: Dashboard 2

Figure 8: Swim Lanes (the pull planning session, "live")

Figure 9: Plan for Today

Figure 10: Weekly Work Plan

Figure 11: Basic Variance Report illustrates the reasons why various commitments were not kept.

At a higher level, the data can be collected enterprise-wide to assess health of various groups or types of projects. The sky is the limit; it’s just a matter of determining what you want to know, and ensuring the data warehouse is appropriately configured to deliver the needed data.

Why does this matter? What is the takeaway?

Teams operating with Lean intensity are shown to have significantly better results in delivering within budget and on scheduleiv. Continual improvement, waste reduction, and adding value are key Lean tenets. The above insights described three examples of those tenets and illustrated how data analytics made each possible.

Tools that help us to collect, organize and analyze data, pulling from the data warehouse, add value by visually alerting teams of issues and trends early. Because the data is “fact-based” and visual, it is more objective and more easily interpreted. It is likely to be received with a more open mind. It has validated and documented performance metrics, favorable or unfavorable. Communicating among trade contractors, design team and the Owner can be much more productive and transparent, with this formatted insight. The resulting trust and collaboration prompt timely decision-making, helps control costs, and brings the project in on time. When trust goes up, speed goes up and cost goes downv. That adds value.

Our current environment of accelerating technologyvi demands attention to data analytics. Our methods of communicating have been shifted into high gear due to COVID-19. We need to find ways to do more with less. In the AEC industry, we are also experiencing a shortage of skilled workers – both in the trades and in the office. With data analytics, we can leverage our wisdom, teach the incoming generation, and inform decisions moving forward, by providing real-time, organized, visual insights and information to our project teams and leaders. The opportunities to add value are boundless.

How can I get more information?

[1] “Trust Matters: The High Cost of Low Trust”, Autodesk/FMI, 2019, https://www.fminet.com/reports/trust-matters-the-high-cost-of-low-trust/

[1] “Why do Projects Excel? The Business Case for Lean,” a presentation on a study by Dodge Data Analytics and LCI, 2019, https://www.leanconstruction.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/W3GB-Mace-WhyProjectsExcel-LeanBusinessCase-Highlights.pdf

[1] Wikipedia, Analytics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analytics

[1] “The Business Case for Lean”, Dodge Data & Analytics / LCI Study, 2016

[1] Stephen M.R. Covey, The Speed of Trust; the One Thing That Changes Everything, 2008

[1] Thomas L. Friedman, Thank you for Being Late: An Optimist’s Guide to Thriving in the Age of Acceleration, 2016

About the Author

Betty Lynn Senes, Project Director, Sundt Construction

Betty Lynn Senes, Project Director, Sundt Construction

With 25+ years in the construction industry, Betty Lynn brings a diverse skillset in collaborative deliveries that leverage high performance teams. Having served roles in operations, estimating, and business development, she understands the critical combination of technical competency and trusting relationships that drive performance. As a lifelong learner, Betty Lynn strives to raise the bar on each subsequent project, infusing Lean concepts each project. While managing higher education, food service, commercial office and hospitality work, she developed an appreciation for the value-add with collaborative deliveries. As Project Director for Sundt Construction, Betty Lynn shepherds projects from the earliest stages through design and construction process, and ensures that the team has the necessary resources it needs to meet the daily demands of the project. Interested early in design-build, Betty Lynn managed multiple projects with design-build MEP trades before design-build picked up traction in the early 2000’s. Betty Lynn has served DBIA as Programs Chairman and Chapter Chair for Los Angeles/Orange County, and has served on the DBIA-WPR Board of Directors for the past three years. She earned her LEED AP and Assoc. DBIA., an undergraduate degree from The University of Connecticut, and an Executive MBA from Chapman University.

»»»»

August, 2020 - LEAN IN DESIGN-BUILD SERIES

How to Use Set-Based Design and Choosing by Advantages Decision-Making in a Design-Build Environment

By Ron Migliori, SE, Buehler Engineering and Steve Wilson, HMC Architects

As we work to leverage the full potential of design-build, this blog focuses on how we can enhance the value proposition that can be delivered through a different approach to design, namely the use of set-based design and the Choosing by Advantages decision-making process.

Set-Based Design

Set-Based Design is a design methodology that evaluates alternative solutions to a design problem or problem statement for consideration. The set of options can vary from a few alternatives to many. The sets get reduced at certain decision gates by developing a deeper understanding of the problem and project constraints ultimately arriving at the best alternative. A deeper dive into the attributes and advantages of the remaining options is often conducted by a Choosing by Advantages decision-making methodology. Only after collaborating with the key project stakeholders does a single solution emerge.

Set-Based Design provides the opportunity to make value-based decisions at the right times in a project. The process is applicable for all procurement methodologies but produces the most value in an integrated and collaborative environment like Design-Build. The process is enhanced when designers and builders can collaborate on design and construction solutions. It promotes innovation and big ideas while incorporating a sound methodology to evaluate the possible solutions.

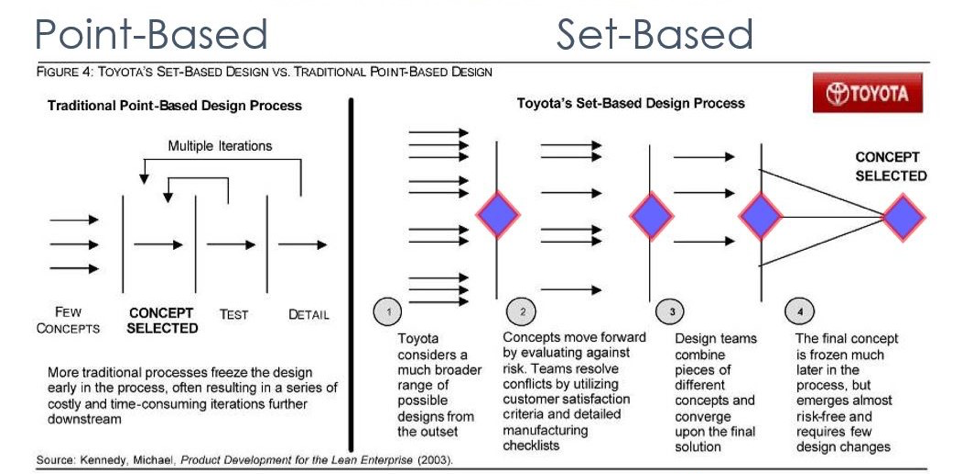

Rather than a linear point-to-point-based design process where a system is selected based on a preconceived idea or “what I did last time”, a series of sets can be leveraged for the benefit of each project’s parameters. In a traditional design-bid-build procurement methodology we commonly see loopbacks or waste in the design process.

For instance:

The figure above shows the difference between point-based and set-based approaches to design.

The timing for engaging Set-Based Design is important and should be encouraged to start as early in the design process as possible. Even if the program is not fully vetted a “strawman” assumption can be utilized as a basis to begin the evaluation process. By utilizing the Last Planner® System and Pull Planning, the team can determine the Last Responsible Moment or critical decision points where a solution is required to advance the design or construction. If sufficient time is not allocated there will be missed opportunities. In Set-Based Design the slogan “Go Slow to Go Fast” means taking a thoughtful approach to Set-Based Design and evaluating potential solutions early in the design process. Once these decisions are made it leads to accelerated design development and implementation without the fear of rework.

As a structural engineer we see system selection sets that include structural gravity systems, lateral load resisting systems, foundation systems, and other structural components where there are multiple viable alternatives. But we also see in our projects mechanical system sets, operational options, building façade and skin systems, building addition siting options, master plan options, and many more alternative sets for consideration. These sets can be based on potential efficiencies in cost and schedule, improved quality and jobsite safety, opportunities for pre-fabrication, or operational efficiency. But to narrow the sets we need a sound methodology to evaluate the alternatives. We find that using the Choosing by Advantages decision-making system allows us to do so in a robust, sound manner.

Choosing by Advantages Decision-Making

Choosing by Advantages (CBA) is a decision-making system developed by Jim Suhr while with the U.S. Forest Service. You can learn more at Jim’s Institute for Decision Innovations http://www.decisioninnovations.com/.

While many decision-making methods are flawed, this system evaluates alternatives by looking at the advantages of each option—ultimately leading to higher quality decisions.

CBA acknowledges all decisions are inherently biased—but then guides the contributors towards basing the partiality on what is empirically verifiable.

CBA includes methods for virtually all types of decisions, from very simple to very complex. Perhaps the most used CBA method is the Tabular Method, which is used to choose among two or more mutually exclusive alternatives that are not equal.

When appropriately applied by decision-makers (designers, contractors, and owners), CBA provides for collaborative visual and open decision-making.

With CBA, decision-makers can reach consensus, focus on outcomes, and understand all the factors considered during the decision-making process.

By utilizing this collaborative system in evaluating the alternatives, it provides a systematic and transparent process to involve key stakeholders. This multi-disciplinary group generates critical factors and their corresponding criteria that may produce an advantage for any of the alternatives. After the alternative's attributes are determined, the advantages are defined. The importance of the advantages is weighed against the target values and the Conditions of Satisfaction (CoS). The CoS is developed by the owner, user groups, and the Design-Build team and defines the values for the project. After all of the advantages are weighed, they are summed to provide the total importance of each alternative's advantage.

"We believe that sound-decision making skills are important for everyone; and, that sound-decision making skills are especially important for people who make decisions that affect other people." – Jim Suhr

Cost is a separate consideration, which is most often considered last after evaluating attributes. So, even if an alternative has the greatest advantage, it does not necessarily make this alternative the selected solution. But it does help to inform the decision once the costs are considered. This is the value proposition where advantages are considered and then weighed against cost. So, if the alternative with the most significant advantage is the least cost or the cost is neutral, it's an easy decision. However, if the alternative with the most significant advantage has the highest cost, a deeper understanding of those advantages must occur. One can always use a cost per point approach, but beware of making the assumption that it automatically makes the decision for you.

Within the CBA system, a common understanding of vocabulary is essential. CBA terms are defined as:

Alternative - Two or more people, things, or plans from which one is to be chosen

Factor - Element, part, or component of a decision

Criterion - Any standard on which a judgment is based – must or want

Attribute - Characteristic, quantity, or quality of one alternative

Advantage - The beneficial difference between Attributes of two Alternatives (one of which is the least preferred)

Anchoring - All decisions, attributes, questions, and importance must be based on (anchored to) relevant factual data.

Importance - Stakeholders' impression of the value of an advantage to meeting the goals of a project

The Lean Construction Institute (LCI) shares that CBA is based upon the following four principles::

During the CBA process (step-by-step instructions):

CBA is good when multiple variables need to be considered to make an informed decision. This will help the team work through multiple solutions to determine the best outcome.

CBA Examples

The following are a couple of examples of the value proposition that can occur in the CBA process.

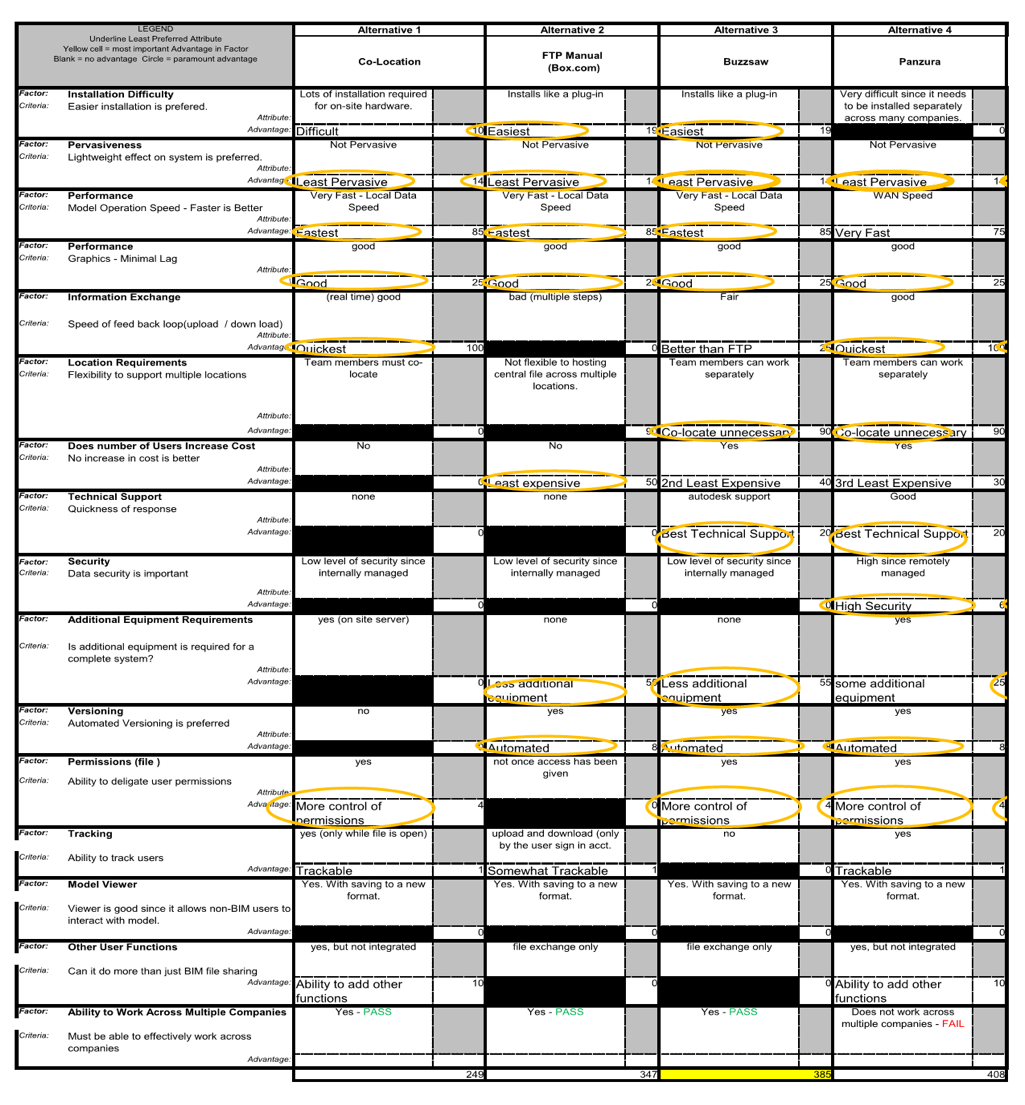

Example #1: Selection of the best collaboration platform for a project. Each team member came with their own bias of which one would be best usually based on knowledge of the software and years of use. In most cases, the general contractor would make a final determination based on their favorite. Cost also plays a factor in licensing and maintenance. The team established a list of factors they consider essential to the overall successful use of the platform in supporting the team. Factors such as installation difficulty, performance, does the number of users increase cost, security, versioning, etc. were considered. In all, the team developed 16 factors to guide their decision.

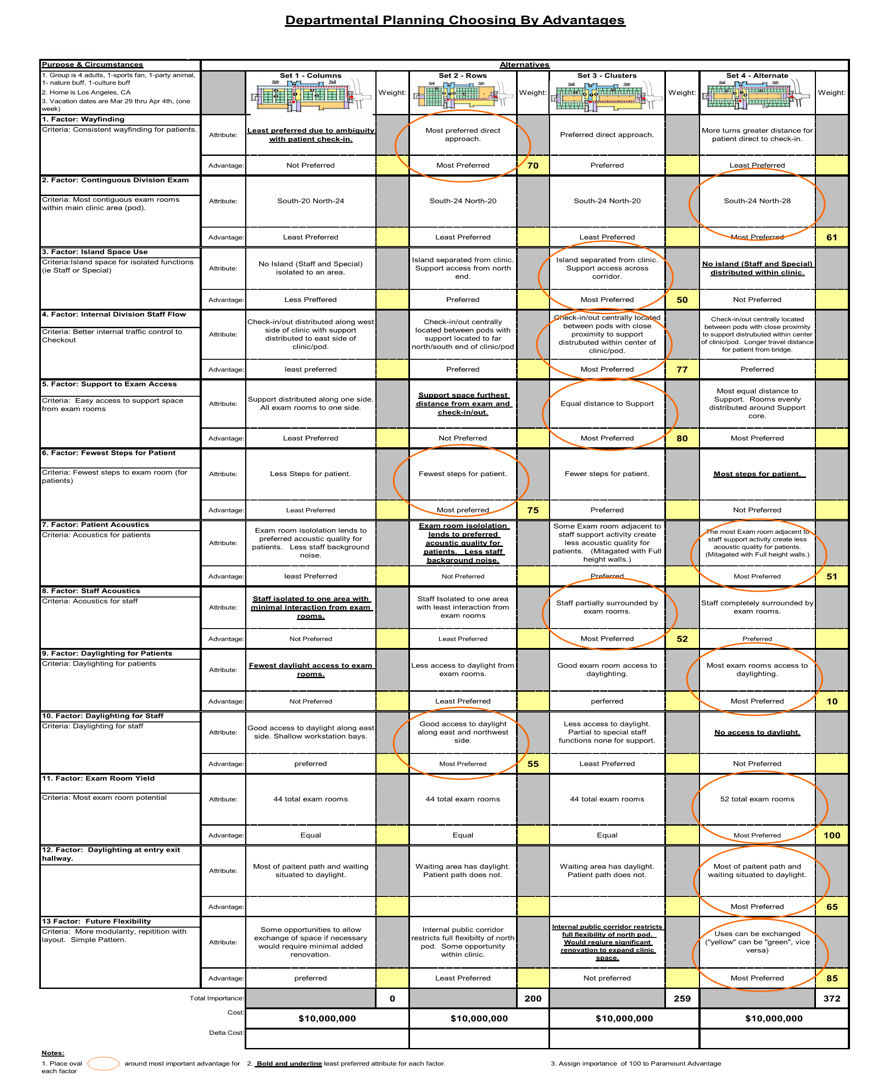

Example #2: Fourteen (14) different outpatient services departments needed to agree on a standard department layout that each would use in a 61,000-square-foot remodel. Each department would provide their conditions of satisfaction, and four planning options were reviewed utilizing CBA to determine which plan would address all departmental needs. Factors such as Wayfinding, Contiguous Division Exam, Internal Division Staff Flow, Support to Exam Access, Fewest Steps for Patient, and Patient Acoustics were weighed to make the final determination. All departments felt their concerns had been addressed and documented.

The stakeholders were reminded that in the CBA selection process, it's critical that they have an open mind without a pre-determined solution. This allows for an open and transparent discussion to get to an agreement on the valuation of the advantages. There are techniques in the CBA process to remove the bias when weighing the importance of the advantages in order to drive to consensus.

In Summary

CBA decision-making can be viewed as a communication tool for the various stakeholders. The discussions that come out of the evaluation of the alternatives is typically an expression of value from each stakeholder's position. Stakeholders view the alternatives the same way, and the negotiation, understanding, and consensus created by this collaborative method of decision-making tend to make lasting decisions that are more durable and easier to communicate. Bias typically has an experience attached to it, so it is not always a negative in this process. CBA is a logical process to vet that bias against the project's value proposition.

When using CBA to make critical decisions, teams can transcend bias (known and unknown) to make fact-based decisions. The process provides for and opens a dialog that takes into account the concerns of all the stakeholders, along with the project's conditions of satisfaction. It also serves as a document that allows the team to review decisions to understand the facts behind the selected solution. A sound value-based decision-making process like Choosing by Advantages can be a vital tool in a collaborative delivery process like Design-Build.

About the Authors

Ron Migliori, SE, Buehler Engineering, Inc.

Ron Migliori, SE, Buehler Engineering, Inc.

Ron is a Past President and current Board member for DBIA Western Pacific Region and LCI member (NorCal Core Group Member Emeritus). Over the past 10 years Ron has been the lead structural designer and Lean champion on approximately two dozen IPD projects and numerous design-build projects. His passion and focus over these years have been on Lean project delivery. Ron has conducted workshops, training, and facilitated many Lean concepts and tools. As a leader in the industry he has presented at LCI Congress, DBIA National, LCI Community of Practice Chapters, and the Lean Design Forum.

Steve Wilson, Associate DBIA, HMC Architects

Steve Wilson, Associate DBIA, HMC Architects

Steve is a principal and member of the board of directors for HMC Architects, HMC’s Non-Profit Designing Futures Foundation, and the DBIA Western Pacific Region Board of Directors. Steve resides in the HMC Ontario studio. With more than 28 years of experience, Steve specializes in healthcare facility design and project management, along with industrial and educational projects

Steve is adept at leading innovative healthcare teams to create design solutions for the evolving healthcare market, and he remains passionate and dedicated to healthcare design and its power to positively impact individuals and communities. For Steve, designing for healthcare is about enhancing the services provided, and thereby positively impacting patients, families, and communities through design. While dedicated to patient-centered design, improving operational efficiencies within hospital settings, he understands the new challenges of delivering more exceptional care at a reduced cost.

»»»»

May 2020 - LEAN IN DESIGN-BUILD SERIES

HVAC PRE-FABRICATION OPPORTUNITIES TO REDUCE COSTS AND IMPROVE SCHEDULE PERFORMANCE

By Brian Coday, PE, DBIA, LEED AP

Duct Risers

Just a few years ago the topping out milestone of the typical construction of a multi-story building (concrete or steel) was celebrated when the structural framing system reached completion and wall framing began. In between these scopes, there would be the duct shaft riser installation, which required a dedicated amount of time due to accessibility. The fact that sheet metal fabrication shops’ coil lines could only make duct pieces a few feet long, HVAC companies used to send all the individual pieces to the jobsite to be assembled within the shafts themselves. By positioning a beam and winch on an upper floor (or roof), sheet metal trades would install the duct riser piece-by-piece (typically 3-4 pieces per floor), either by building it from the lowest floor up or by lifting the whole riser within the shaft and sliding a new piece onto the bottom, repeating the process until complete. The time impacts to the schedule with this riser installation being sandwiched between other scopes would create frustration and, in some cases, unplanned overtime, weekend work, and possible schedule delay notices.

Today, duct risers are pre-assembled at the shop into longer segments and hoisted into place in a matter of hours, saving overall project time and possible delays. View a short video at this link. The length of the truck bed is utilized as the limiting factor of what can be delivered from the facility, rather than the number of fittings. Welding lifting brackets to the duct brings further efficiency to the rigging process, such that the trucks can drive in and be offloaded quickly. By reducing this duct riser installation time, both shaft framing as well as roofing activities for the top-of-shaft flashing details are able to get an earlier start. For metal deck buildings, these risers may be installed before all the concrete is even poured.

Distribution Ductwork

Horizontal ductwork has also been optimized with pre-fabrication. Through the use of BIM coordination and confidence in clash avoidance, horizontal duct can now be spooled and sectioned before arriving onsite. This reduces field time as compared to the shop sending ‘some straight duct and a bunch of fittings’ which was the old mentality.

Pre-Packaged Skids

Pipe fitters have taken to prefabrication as well and have seen efficiency improvements. Heating Hot Water skids with boilers and pumps are being pre-piped, insulated, and rigged into place as a single unit. By having all the accessories piped together in a controlled environment, a crane simply lifts the skid into position and the field craft only has to make connections. Coil connections and valve-trains are also prefabricated reducing the need for field resources. The result is less stacking of trades and jobsite congestion. Prefabrication approaches also reduce the overall craft field installation labor hours which can pay dividends within high-rise projects or projects in large cities where manlift congestion and parking fees apply.

Pipe fitters have taken to prefabrication as well and have seen efficiency improvements. Heating Hot Water skids with boilers and pumps are being pre-piped, insulated, and rigged into place as a single unit. By having all the accessories piped together in a controlled environment, a crane simply lifts the skid into position and the field craft only has to make connections. Coil connections and valve-trains are also prefabricated reducing the need for field resources. The result is less stacking of trades and jobsite congestion. Prefabrication approaches also reduce the overall craft field installation labor hours which can pay dividends within high-rise projects or projects in large cities where manlift congestion and parking fees apply.

Along with the mechanical improvements realized from prefabrication, horizontal utility support systems like all-thread and clevis hangers are being installed around shoring (rather than waiting for shoring removal), drain piping is getting installed before beams get coated with fire-proofing, and early fire sprinkler installation is happening. These early-starts allow a jump into the true rough-in phases rather than having a building sit idle while the concrete cures.

Overall, the ‘topping off’ milestone still occurs on most projects, but has since been decoupled from other scopes starting. With the rigging of prefabricated duct risers, as well as early starts by other trades, there is a more reliable work flow production in the field and less stacked manpower.

Considerations

To fully realize these opportunities here are some considerations when planning:

DUCT RISERS

HHW SKID

Brian Coday, PE, LEED AP, DBIA, Project Executive, Critchfield Mechanical

Brian Coday, PE, LEED AP, DBIA, Project Executive, Critchfield Mechanical

Brian started working with Critchfield Mechanical, Inc. in 1998. From the office campus booms of the late 90’s to multi-use neighborhoods and hospital work in the early 2000’s, he grew within the company as a mechanical design-builder. In 2006 he moved to Honolulu to help a new branch office Critchfield Pacific, Inc., but then returned ‘home’ in 2016. Now he works on procuring and delivering high quality projects such as P3s, residential, and commercial buildings. Brian has been a member of the DBIA Western Pacific Region Board since 2011.

»»»»

Archive: February 2020 - LEAN IN DESIGN-BUILD SERIES

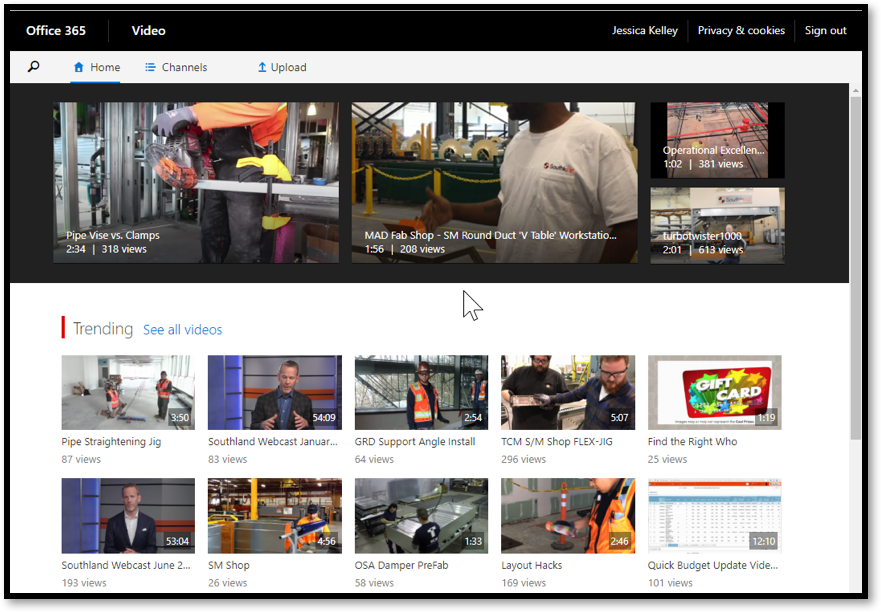

Establishing a Lean Culture in an Organization, the Southland Industries Story

By Jessica Kelley and Joe Cvetas

The steps to establishing a Lean Culture are no different than establishing any other cultural aspect within your company. What is it? Why are we doing it? And where do we want to go with it? Organizational culture is often created in one of three ways, deliberately, organically, or a hybrid of the two. For Southland Industries, a leading Design Build building lifecycle solutions company (which includes engineering, fabrication, construction, service, building automation, operations & maintenance, and energy services), developing a lean culture was deliberate in intent and organic in the evolution.

As a founding member of the Lean Construction Institute(LCI), Southland saw the benefit in delivering projects differently to provide more value to our customers by delivering projects faster, at a lower cost, and with higher value. We were able to build on our existing culture of innovation and quality, where we created a work environment that empowered our people to be innovative problem solvers. Southland is no stranger to progressive delivery models, whether it is being a leader in Design Build or Integrated Lean Project Delivery, it takes strength of conviction and deliberate commitment by company leadership to create a culture that is unique from the greater industry to sustain through market challenges, organizational growth, or limited customer pull.

Though some cultural concepts can be black and white, a Lean Culture is a spectrum that incorporates continuous learning and capitalizing on opportunities enabled by the business environment. In 1998 “Lean Construction” was primarily based on Greg Howell and Glenn Ballard’s research around workflow and production planning, what became the Last Planner® System (LPS). So that is where Southland started, implementing 3-week lookaheads, Weekly Work Plans and reflection through Planned Percent Complete (PPC) and Variance tracking. We did this independently on projects and attempted to show other Trades and General Contractors the benefits of detailed short-range planning and reflection to improve the greater project planning effort. Enlisting our foremen was directly aligned with our culture of empowering the front line to own the planning and execution of their work, which is also a necessity of the Design Build delivery method which has an overlap of the design and construct phases of a project and often prohibits full project scheduling at the beginning of the construction phase. We then transferred this empowerment of our front line to make improvements in their work. Before the “fix what bugs you” tagline attributed to Paul Akers for making 2 Second improvements we had the “SI Way” or “Simply Innovate” campaign to encourage our employees to own their work and make improvements, large or small, because those that do the work are often best equipped to improve the work.

This helped them see that we trusted them to take action and knew that the often-considered little things add up to great improvements. This took away the perceived shackles and opened the flood gates for innovative improvements throughout the business, from the shop and field to design and operations.

In cultural transformation and Lean, the iterative process of the Plan – Do – Check – Adjust (PDCA) cycle is necessary for improvement. The construction industry, unlike manufacturing, is an integrated system that depends highly on the various partners on a project. Applying LPS can only take you so far. To take the next step (adjustment), we leveraged the community the Lean Construction Institute helped create to connect with other like-minded companies that were on their Lean journey as well. People who recognized the dysfunction in our industry and made the commitment to themselves, us, and the greater industry to improve it. We teamed up with Sutter Health, DPR, Boldt, and HGA to see what could be accomplished if we worked together as one to advance Lean on our projects beyond what we were able to do individually. Building off our empowered culture of innovation and improvement, our teams were then able to say “what if” to the full project team with the goal of eliminating waste and frustration in the current delivery models. Leveraging Integrated Lean Project Delivery (ILPD) made it easier for all team members to shift behaviors from the old to the new way of behaving, breaking down dysfunction that purely existed due to the shifting of risk that traditional contracts are based upon. Already having a Design Build culture made it even easier to work in these new ways because we had foremen accustomed to providing early feedback to design for improved constructability, project managers with engineering and estimating skill sets, and engineers that could speak to the various design solutions (flexibility, maintainability, cost). As with any highly collaborative environment, the communication methods and skills needed to be effective are different than what was typically used in more hierarchical, command-and-control contract structures as well as what has been used traditionally in the construction industry. As we recognized these differences, we adjusted how we developed our employees, to make working in the Big Room, more impactful.

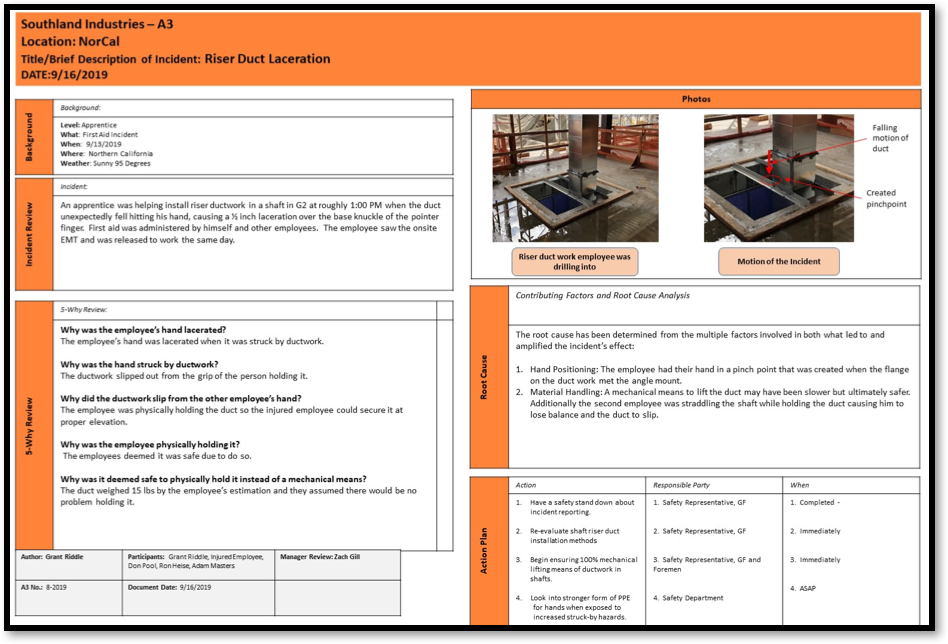

As our journey progressed, so did our assessment of our Lean journey. More people started learning about Lean principles, looking beyond the construction industry for fundamentals, applications, and case studies. We realized that though we were making progress on our projects and sharing our learnings with the greater industry, we still had opportunities to apply greater Lean thinking to our own organization’s operations and to our projects that traditional delivery models limited or outright prevented. Concepts such as Set-Based Design, A3 Thinking and Choosing By Advantages Decision-making helped our teams create better decisions related to design and pre-fabrication opportunities for the owner and the whole team with less wasted effort. We began using A3 reports in our Safety department to rapidly share learning on incidents with the intent to prevent the same or similar incident on other projects or in other regions.

The more we learn, the more places we find we can apply Lean thinking both internally and at a project level. The more people learn, the deeper the understanding of Lean becomes, from empowerment of our people, to continuous improvement, understanding customer value, learning new ways to increase the visibility of waste, and engaging stakeholders to make change stick becomes a relentless pursuit on our Lean Journey.

Jessica Kelley, PE, Operational Excellence Manager, Southland Industries

Jessica Kelley, PE, Operational Excellence Manager, Southland Industries

Jessica started her career with Southland Industries designing and managing design-build-maintain projects. From there she had the opportunity to support and manage Southland’s Enterprise Resource Platform selection and implementation initiative. She then moved on to building the Learning and Development Department and now is focused on Operational Excellence in a full-time capacity. Jessica has been actively involved in the Lean construction community from the start of her career, driving efficiency and focused improvements internally at Southland, on projects, and in the industry as a whole.

Joe Cvetas, Executive Vice President of Corporate Development and Planning, Southland Industries

Mr. Cvetas helps set overall growth strategies and goals for Southland leading the company’s mergers and acquisitions approach. He is also responsible for identifying opportunities for entry into new markets and products, the formation of strategic partnerships, and the acquisition of other companies. With over 30 years in the MEP industry, Mr. Cvetas has considerable experience optimizing building systems for a variety of markets and industries. He is also responsible for providing business leadership and oversight for Southland Energy, a division of Southland, and Envise, a wholly owned subsidiary of Southland.

»»»»

Archive: January 2020, LEAN IN DESIGN-BUILD SERIES

One of Lean Construction Institute’s 8 Wastes: Under-utilization of Talent

Diane Anglin, Project Communications Executive

Clark Construction Group

2018 Past President, DBIA Western Pacific Region

The total value of a team’s strength is the sum of its applied knowledge, expertise and creativity. The key word is applied. Tapping into that full capacity of the team is one of the great challenges of the management of teams. Principles of Lean in design and construction identify the under-utilization of talent as one of the eight main areas of common wastes. "It is the biggest waste of all, the one that can hurt the most, and often gets thrown to the side and completely ignored.” suggests Bigelow, in the ISixSigma community blog.(1)

With integrated forms of delivery, we put in place organizational structures to aid in the collaboration of our teams and begin to tap into the team’s talents. Structures such as partnering, teaming agreements, and co-location have been used successfully for many years, yet fully utilizing talent continues to be an opportunity to reduce waste. Where are we missing the mark? How could we discover what talents are going untapped?

Melding of Cultures

One of the more compelling strategies that I’ve come across for combatting this area of waste is addressing the melded culture that exists when team members come together. A potential root cause for waste is not so much found in the structures that are in place but the different culture that each team member brings to the team.

In project-based teams, when members are brought together, each brings with them existing cultural norms and established mental models that have taken root over the course of their very specific experience. As positive as they may be, there will be tensions between existing personal cultures/behaviors and attempts at setting new ones for the team, and can lead to waste in the time it takes for team members to be fully effective organizational members. The Lean Construction Institute (LCI)’s onboarding process goes a long way in addressing this area of waste at the earliest moments of a project. (2)The onboarding process reinforces how intentional steps must be taken to assist team members with adapting and sometimes even unlearning their own cultures in order to accept a new team culture. LCI’s knowledge paper on onboarding offers “onboarding, also known as organizational socialization, is a way for new employees to quickly acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and behaviors to become effective organizational members.”

I asked Lean Coach Terri Erickson with Kata Consulting to comment on the importance of onboarding. “By providing a deliberate onboarding experience for all team members, they are given an opportunity to participate in forming the “rules of the game” for the structure of the project. This helps them develop a deeper understanding of these rules and may help them avoid inadvertently doing something that may not be in alignment, or worse losing face or digging in heels.

This process of onboarding demonstrates a Lean value of deep respect for the individuals participating on the team by allowing them a safe environment to re-calibrate to a new way of working which may be different than the ways they have worked in the past.

One way, as a Lean Coach, that I have improved this onboarding experience is to meet with each trade partner individually ahead of time to provide basic Lean training and discuss the first team meeting, prepare them for it, and answer any questions they may have. By taking this extra step in the beginning they are equipped with the confidence to “hit the ground running” as a participant in the collaborative team forming process.”

Untapped Talent

Authoritarian project management models can motivate leaders to have a good plan – first and foremost and lead by providing clear direction and control. Subscribing to this, unwittingly the manager may be contributing to the under-utilization of talent in their team. This can set up a mental model that in order to be worth his/her salt, they need to show up with a fully cooked plan. This process in effect, shuts out team input, and reinforces a lack of recognition for the talent of the broader team. An action as simple as problem solving alone in a vacuum, can establish a culture of individualism versus collaboration with the pool of talent and expertise of the team going untapped and underutilized. With supervisors handling the problem solving, many employees don’t believe they are expected to be creative. This perpetuates a “knowing culture”, versus a establishing a “learning culture”. Learning cultures acknowledge that team members are a vital part of the equation for developing any plan. It should never be cooked alone.

A Manager’s Influence

The culture that is set by the manager matters. The influence that the manager(s) has on the engagement of team members may be even larger than typically thought. Gallup’s largest global study of the future of work found that “one of Gallup’s biggest discoveries is: The manager or team leader alone accounts for 70% of the variance in team engagement.” So much so, that Gallup titled the book on this study as “It’s the Manager” and states, “the need for disruption in how employees are managed couldn’t be more urgent” and offers instruction for managers to transition from “boss” to “coach”. (3)When managers spend more time coaching and guiding it can make a profound difference on the engagement and contributions of team members.

For engaging team members on collaborative projects, what is required is a different kind of project manager asserts Bill Seed, SVP Jackson Health System, whose white paper outlined a new skillset needed for successfully managing integrated projects. “The Integrated Project Manager must encourage the collaborative solicitation of need, input and output from all members. They must build trust and respect amongst team members. They must drive constructive conflict so that all ideas/concepts are presented, discussed, openly considered and either implemented or discarded.” (4) In this way the leaders pull in certain team members appropriately to tackle problems specifically in the areas where their feedback can lead to solutions and improvements. Lean approaches such as cluster groups can provide the structure to help add multi-discipline interaction into the project’s cadence.

Avoid Group Think

How does the size, and makeup of the team influence its collective abilities? If all team members look and act the same and come from similar backgrounds and roles, their expectations may be limited on the amount of impact they think they could have on the team. A group phenomenon termed “Group Think” (5)can take hold of the team’s decision-making abilities unless leaders actively seek to counteract it. Group Think has been attributed to inadequate risk evaluations, lack of creativity and lack of contributions by individual team members. Suppression of individual opinions and creative thought can lead to poor decision-making and inefficient problem-solving. In a group environment that lacks diversity, illusions of unanimity can lead members to believe that everyone is in agreement and feels the same way, and therefore they limit their input. (6) Diversity is an element of team formation that can make a real difference in the utilization of talent of the team.

Archive: November, 2019, LEAN IN DESIGN-BUILD SERIES

Lean in Design-Build – The Untapped Potential

By David Umstot, PE, Umstot Project and Facilities Solutions, LLC

2015 Past President, DBIA Western Pacific Region

This is the first in a series of blogs on Lean-related topics that the DBIA Western Pacific Region has developed to help our membership understand what Lean is and how we can leverage Lean in the integrated nature of design-build projects to deliver even better projects. You may already have an understanding of Lean, or you may not even have heard of Lean. Our goal in these series of blogs is to help educate our DBIA members to develop a fundamental understanding of Lean as it applies to design and construction and to challenge our members to look for ways to create value through more effective collaboration, elimination of waste, and continuous improvement. Let’s start our Lean journey with a short assessment of where we are as an industry.

The Construction Industry - Current State

Our industry is confronted by challenging times. The quadrennial American Society of Civil Engineers 2017 Report Card on American Infrastructure gives the nation’s infrastructure an overall grade of D+. The report card estimates $4.59 trillion will be necessary to invest in our infrastructure by 2025 to meet our needs. To complicate matters, there is an expected funding gap of more than $2 trillion. It is unrealistic that our nation will be in a position to create an additional $2 trillion in funding over the course of the next few years to address these needs. So that begs the question “Is more funding the answer, or is the solution using the available funding in a manner that yields greater value?”

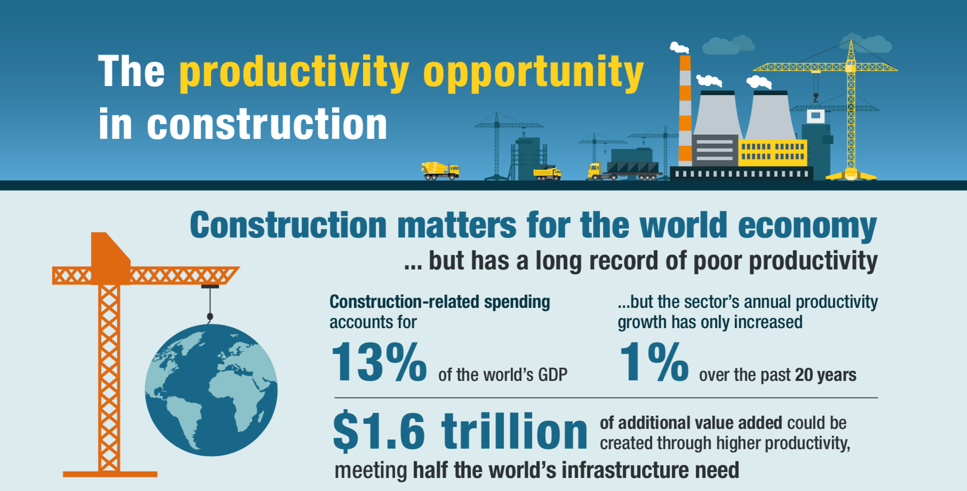

McKinsey published a study in 2017 titled Reinventing Construction: A Route to Higher Productivity. McKinsey shares that while construction-related spending accounts for 13 percent of the world’s Gross Domestic Product, there is a $1.6 trillion annual gap of additional value that could be realized if the construction industry were to simply match the productivity growth rates of the manufacturing and service sectors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Productivity Opportunity in Construction (Source: McKinsey - 2017)

To compound matters we have an aging workforce and shrinking craft labor pool. We cannot expect to meet the world’s infrastructure and building needs with past practices. We need to take a fresh look at how to better deliver our design and construction of projects. Which takes us to Lean and a Lean mindset.

Lean – What is It?

The origin of Lean is in the manufacturing sector and specifically the Toyota Production System. While we do not design and assemble cars, Lean is directly applicable to design-build. Let’s look at some of the fundamentals and how they relate to design and construction.

Firstly, the foundation of Lean is built on respect for people. People design and build buildings. How do we leverage the centuries of cumulative experience on projects to the benefit of the project and to add the most value?

Value is central to everything in Lean. Identifying the value stream is key. Specifically, we need to start with understanding what the customer values. What is important to the customer? What are they willing to pay for it? Things the customer does not value and is unwilling to pay for constitute waste. Our industry is laden with waste and there is ample opportunity to do better and create more value for our customers and in turn their internal customers on a project. Learning to see waste is the first step.

Once the value proposition is understood, Lean allows us to apply systems to enhance the flow of production. This could be flow of information and progression of a design package, flow of material and labor in a pre-fabrication environment, or production on-site with trade contractor material, equipment, and labor. The greater the reliability and predictably of flow, the better the production rate. We will learn in future blogs more about the Last Planner® System and how it can be used for production planning to effectively identify and manage handoffs between the more than a dozen design disciplines and multitude of trade contractors on a project to better enhance flow of work. While we are very good at our own disciplines and areas of expertise, we collectively do a poor job of integrating across these disciplines. This is where much of the waste occurs in design and construction.

Let’s discuss one of the biggest impediments to value generation in our industry - waste. Waste is defined by dictionary.com as “an act or instance of using or expending something carelessly, extravagantly, or to no purpose.” There are 8 wastes in any production system. Let's look at each of these in the context of our project delivery process with examples:

Doubtless you have experienced and witnessed examples of waste on your projects regularly and most probably on a daily basis.

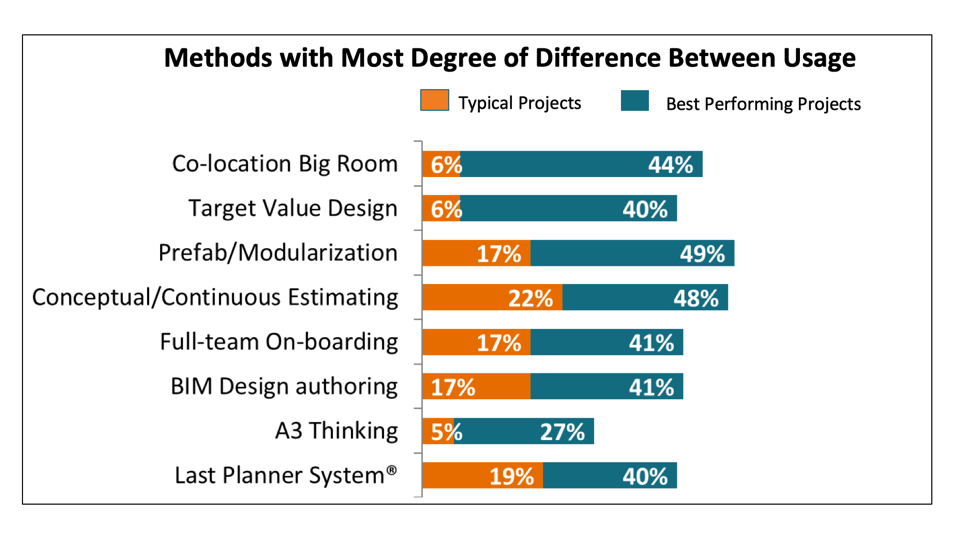

The Business Case for Lean – The Owners’ Perspective

In 2016, Dodge Data and Analytics conducted a study of 81 owners in the United States with large construction portfolios asking them to share the characteristics of the best project they had ever delivered as an owner and those of their typical projects. The results of the study showed that projects using Lean practices with high intensity were 3 TIMESas likely to finish ahead schedule and 2 TIMESas likely to finish under budget. How do we make that performance level consistent? We can achieve this by integrating the Lean practices shown to have the greatest impact based on the greatest degree of difference between best and typical projects shown in the chart below (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lean Practices Used with Greater Frequency on Best Performing Projects

(Source: Lean Construction Institute - 2016)

Future blog posts will address each of these Lean practices in more detail.

In 2017, a joint working group was developed with members from DBIA and the Lean Construction Institute to explore how best to develop awareness and greater Lean adoption as part of design-build project delivery. As part of this effort, a cross-map was developed between the DBIA Design-Build Done Right: Best Design-Build Practicespublished by DBIA in 2014 and Lean practices. It is available at this link.

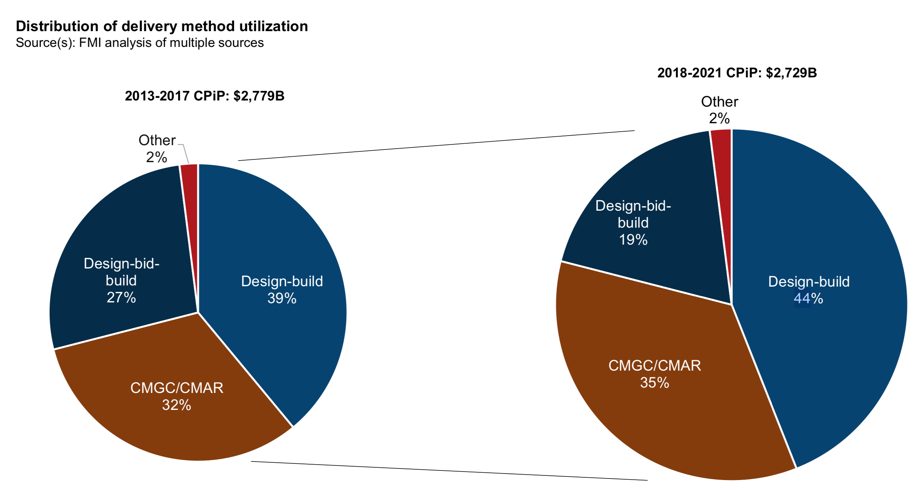

Progressive Design-Build and Lean

As the Design-Build community moves towards greater use of progressive design-build, the opportunities to integrate Lean into the way we design and deliver projects are significant. Design-build delivery is projected to represent 44% of the non-residential construction market by 2021 based on a study by FMIpublished in June 2018 (Figure 3). With this market share, the potential to reach a tipping point in the way we deliver our projects using Lean is within our grasp.

Figure 3. Percentage of Non-Residential Construction Delivered by Design-Build (Source: FMI-2018)

Now that you have some knowledge, what are you going to do about it?

“The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones.”- Confucius

»»»»